Slate has relationships with various online retailers.

If you buy something through our links,

Slate may earn an affiliate commission.

We update links when possible,

but note that deals can expire and all prices are subject to change.

All prices were up to date at the time of publication.

In July and August of 1961, Johnny Cash recorded a batch of songs that became the basis for Blood, Sweat and Tears, a record many regard as merely a concept album about working people. But Blood, Sweat and Tears is a concept album about race in America, about the violent enforcement of racial hierarchies in America. It is the one great record made in support of Black lives by a country music star, even if almost everyone missed its message when it was released. To be fair, when we think of a civil rights album, we think of those freedom songs. If Cash had just recorded his own interpretation of Odetta’s “Freedom Trilogy” or, like Pete Seeger, brought news of the civil rights movement in song to a live audience—getting them to sing along on “If You Miss Me at the Back of the Bus,” “Keep Your Eyes on the Prize,” and “I Ain’t Scared of Your Jail”—it would have been much easier to label Cash as an activist artist, to see the work he was doing. But as musicologist and folklorist John Lomax once argued, folk music could “provide ten thousand bridges across which men of all nations may stride to say, ‘You are my brother.’ ” To put down on record—both vinyl and historical—evidence of the shameful, despicable practices of white bosses against Black men and their families made for a bridge of understanding that better suited Cash’s temperament than the freedom songs. On Blood, Sweat and Tears, he sings of racial bondage, of racial violence, of racist murder. He recorded these songs not to inspire activists so much as to confront his mostly white listeners with the shocking, documented brutality their silence made possible. His civil rights work, if we can call it that, is complementary; he stands as witness.

Side One of Blood, Sweat and Tears possesses such cumulative power, rooted in violence, that it is hard to listen to it twice in a row. One really needs to flip the record to the other side to find some relief, even if it is in limited supply on Side Two. Cash most likely learned original versions of all three of the songs on Side One—“The Legend of John Henry’s Hammer,” “Tell Him I’m Gone,” and “Another Man Done Gone”—from Lomax recordings (though, in the case of “John Henry,” there were dozens of versions out there already). But, in each case, Cash arranged, adapted, and added his own lyrics.

Cash begins the album with an eight-minute version of “John Henry,” following in a grand tradition of interpreting and reinterpreting the song about the steel drivin’ man. In Merle Travis’ downhome introduction to the song on his album Folk Songs of the Hills, he says that people from different parts of the country—coal miners in Kentucky, ironworkers in Birmingham, railroad workers out West—have tried to claim John Henry. “I don’t know myself where in the world John Henry came from,” he says as he begins singing, and it is possible that, like a lot of white Southerners, he assumed that John Henry was white. By the time Cash considered recording “John Henry,” the subject’s identity as a Black working man, if not a Black convict, was well known. In their 1941 book, Our Singing Country, John Lomax and his son Alan described the “ballad of John Henry, the Negro steeldrivin’ man” as “probably America’s greatest single piece of folk lore.” Later, in the liner notes to Blue Ridge Mountain Music, one of the seven LPs in the Southern Folk Heritage Series that Cash committed to memory, Alan Lomax repeated that the Mountain Ramblers’ version of the song tells the story of “the Negro tunnel worker … who drove the steam drill down in a contest of the ‘flesh against the steam.’ ” Years later, when Cash made a 1974 television program called Ridin’ the Rails, he devoted two segments of his history of the railroad to honoring the work of Black men, showing gandy dancers and section men laying track, and John Henry himself (played by a Black actor) swinging a hammer. There is no question that Cash understood in 1962, as he sang about John Henry, he was singing about a Black man. We know today that John Henry was a real man, pushed into convict labor on a thin charge the way so many Black men were in the years after the Civil War, and who died on the job (though not before driving more steel than the steam drill). But even by 1962 there had been plenty of representations of John Henry wearing a ball and chain—enough that Cash, poring over Library of Congress recordings, could not have missed it.

Try listening to several versions of “John Henry” in a row—particularly Merle Travis’ upbeat picking rendition, Odetta’s more somber version, and Cash’s treatment at the end—to get a sense of how varied the interpretations of the song can be. At the time that Cash recorded the song, he was in the unyielding clutch of his drug addiction. Marshall Grant remembered him sitting on the floor banging pieces of rolled steel together to get the sound of the hammer hitting; he was so high he beat his hands bloody, apparently feeling no pain. In spite of his condition, his “John Henry” sounds like a continuation of the work he did on Ride This Train—not only because he again mimicked sounds from the field, as if to make it seem more authentic, but because in his delivery he is as much a narrator as a singer. But Cash doesn’t sound squeaky-clean, the way Merle Travis drifts into folkcrooner territory; instead, Cash builds momentum in the song, the way Odetta does, as the story reaches the part about the race between John Henry and the steam drill. Although Cash’s rendition of “John Henry” on Blood, Sweat and Tears is undermined somewhat by the shape he was in when he recorded it (the editing together of two separately recorded parts is obvious), the song became a standard part of his show so that by the time he recorded it again at Folsom prison in 1968, it had to be considered one of his best.

Blood, Sweat and Tears is a landmark achievement in the contemplation of race by a country music artist, even if Columbia did not market it that way.

Cash follows “The Legend of John Henry’s Hammer” with “Tell Him I’m Gone,” a retitled, rewritten version of Leadbelly’s “Take This Hammer.” Just as a chef who changes more than three things in a recipe can claim the recipe as his own, Cash must have figured that he altered enough of the lyrics to justify a new title. The Lomaxes’ 1942 recording of Leadbelly singing “Take This Hammer” is pretty straightforward. It is the tale of a man fleeing from the chain gang, telling the new guy to whom he is giving his hammer to pass along a message to the boss, the captain: “Tell him I’m gone.” He doesn’t say much about why he is leaving except that he no longer wants “cornbread and molasses” because, he says, “it hurts my pride.” In fact, the lyrics published by the Lomaxes in Our Singing Country included additional lines such as “Cap’n called me a nappyheaded devil” and “I don’t want no cold iron shackles, around my legs, around my legs,” giving a clearer sense of the singer’s motives. When Odetta recorded the song live, at the Gate of Horn club in Chicago in 1957, she basically used Leadbelly’s version but reintroduced the “cold, iron shackles” line too, which surely helped the audience better see the scene. Perhaps emboldened by Odetta’s edits, Cash added several lines to the song that make the captain more violent, more menacing. There is nothing about the lousy cornbread hurting his pride. He even dropped the “cold, iron shackles” from Odetta’s rendition. Instead, Cash’s prisoner escapes from the chain gang because he cannot take the “kicks and whipping.” He says the captain called him “a hardheaded devil” (a revision of the “nappyheaded devil” line recorded by the Lomaxes), but since that is not his name, he is leaving. In all the previous interpretations of the song, it is pretty clear that the convict is confident he is going to find freedom, but Cash introduces a degree of uncertainty, saying that if the captain ever catches him, “he gonna shoot me down” with his big gun, “about a .99 caliber.” (This, too, is a modification of a line published by the Lomaxes—“Cap’n got a big gun, an’ he try to play bad”—which made it into no other recorded versions.) When Cash sings “about a .99 caliber” the first time, he lets out a “whooooa,” as if the character is both impressed with and deathly afraid of that gun. The howl sounds almost unhinged, desperate, and certainly not confident—like he knows he is risking his life. Taken together, the new lyrics describe an overseer who, as Cash said in “Going to Memphis,” whips convicts like mules, taunts them with names, and has the capacity, thanks to his big gun, to snuff out a convict’s life. As the saying went, “One dies, get another.”

“Another Man Done Gone,” the third and final song on the first side of Blood, Sweat and Tears, effectively tells us what happened to the convict who fled the chain gang in the previous song. The Lomaxes first recorded the song in 1948, as sung by a Livingston, Alabama, dishwasher named Vera Hall. Unlike “Tell Him I’m Gone,” which is narrated by the convict, “Another Man Done Gone” is told from the perspective of a witness to a crime involving the convict.

In Hall’s version, it is the convict who committed the crime, but in Cash’s version the convict is the victim. Hall sings that although she does not know the name of the man done gone, she could see that he came from the “county farm” and had a “long chain on.” The most important line, in comparing Hall’s original version to later renditions by other artists, including Cash, is that she says, “He killed another man.” The man done gone is a killer who, though imprisoned and on a chain gang, has now killed again and is on the run. “I don’t know where he’s gone,” she sings at the end. Odetta recorded “Another Man Done Gone” for her second, classic LP, Odetta Sings Ballads and Blues (1957), a collection of Lomaxian proportions with some songs drawn from their book Our Singing Country. But instead of singing, “He killed another man,” Odetta changed it to “They killed another man,” and she dropped the line about not knowing where he has gone; it’s apparent that in this rendition our narrator knows that the man being “done gone” means he is dead, killed by those who chased him from the county farm or the levee or wherever else they may have worked him so hard he fled. A year later, Leon Bibb, a less-wellknown Black folk singer who was a mentor to Odetta, added another line to the song—“They hunted him with hounds”—which dispels any doubt about what happened to our convict. Cash doubtless knew all of these interpretations and may have even been inspired by Bibb’s introduction of a new line when he thought about recording his own.

Cash’s version of “Another Man Done Gone” is simply the most harrowing on record. Except for a single opening strum of a guitar, Cash sings the song a cappella (like Odetta and Vera Hall), but his baritone sounds as though it is coming from the bottom of a well, resonant with a bit of echo; it contrasts, in call and response, with the crystal-clear soprano of Anita Carter. Cash’s and Carter’s voices complement each other and lend a gothic feel to the original story. In Cash’s telling, there is no mention of hounds; instead, he skips directly from “he had a long chain on” to “they hung him in a tree.” Worse than that, “they let his children see.” These are Cash’s lines, and he alone sings them. Carter repeats most of the lyrics sung by Cash, but not these about the lynching. It’s as if the fragile purity of her voice cannot bear the weight of what our narrator has witnessed. But even here, Cash is not satisfied that his listeners will fully understand what he seems to have grasped—maybe from his Arkansas boyhood, maybe from family stories—about the repulsive evils of lynching. “When he was hanging dead,” he sings in his lowest register, “the captain turned his head, the captain turned his head.” The scene of a man’s lynching in front of his family is so distressing that even the captain, the man who led the lynch mob, cannot bear to look. Cash isn’t aiming for a hit single: he is aiming to turn our stomachs, and not gratuitously either, because he recorded it in the summer of 1962, when violence lurked everywhere. (Just months after the album came out, Klansman Byron De La Beckwith shot down NAACP organizer Medgar Evers in his driveway, in front of his wife and children.) The song punctuates Side One like an exclamation point, insisting that the lives of these exploited Black men, all in chains, mattered.

The second side of Blood, Sweat and Tears lacks the gathering sense of terror of the first, but its tone is still somber. Cash leads off with Harlan Howard’s song “Busted,” which Columbia released as the album’s only single. Howard set the song of a guy who is so poor that “a man can go wrong” in coal mining country, but Cash moves it to the cotton fields. As such, his slow lamentation is more consistent with the songs on the first side; it sounds more like an Odetta song than a Burl Ives (who had previously recorded it) or Ray Charles (who turned it into a hit at nearly the same time Cash released it) song. Cash followed with “Casey Jones,” the well-known folk song about the daring railroad engineer who died in a wreck around the turn of the century. The origins of the song are murky; it is probably a composite of several old folk blues tunes sung by railroad workers, but at the time Cash recorded it, the Lomaxes and others agreed that a Black engine wiper named Wallace Saunders wrote the song. Saunders worked in the Canton, Mississippi, roundhouse and apparently knew Casey Jones. In Cash’s presentation, alongside these other songs of the Black experience, then, “Casey Jones” functions as an example of interracial harmony, a song by a Black engine wiper honoring the memory of a brave white engineer. “Nine Pound Hammer,” the Merle Travis song from Folk Songs of the Hills, is more sober than the original, even as it relies on banjo picking as its signature sound. Cash’s narrator sounds exhausted as he sings. If Blood, Sweat and Tears were merely an album about working people, Cash could have chosen “Dark as a Dungeon” by Travis, but in selecting a song about another hammer swinger, he seems, again, to be singing about a Black man’s 9-pound hammer. The next song, “Chain Gang,” another by Harlan Howard, confirms the theme by describing a guy getting picked up on vagrancy charges and winding up on a chain gang—likely a Black character, given that the overwhelming majority of men railroaded into being convict laborers were Black. “There ain’t no hope on a chain gang,” Cash sings. Unlike the first side of the LP, these songs are more ambiguous about the race of each one’s subject, so listeners could have assumed that the subjects were white. But given Cash’s experience, it’s hard to believe that’s what he thought.

Blood, Sweat and Tears is a landmark achievement in the contemplation of race by a country music artist, even if Columbia did not market it that way. It’s possible that Don Law didn’t fully appreciate what Cash had done with this album, and Cash himself remained strangely quiet. Perhaps he felt compelled to comment on Jim Crow segregation by drawing from the wellspring of Black American folk blues but also felt that, as a white Southerner, he couldn’t directly address it. “I was trying to write about history so that people could understand what was going on,” he said. Cash brought his own experience, his own witness, as an Arkansas white boy, as well as his research to the material. Years later, when he described his fascination with Blues in the Mississippi Night and the Lomaxes’ prison recordings, Cash acknowledged that although he felt comfortable recording some songs from that canon, he couldn’t play them all. One gets the sense that he felt like an interloper, not knowing if it was his place to give voice to some of these songs born of Black pain. And still, he showed no eagerness to speak out beyond his music. At least, not yet.

It would be easy to look from our own vantage point at Blood, Sweat and Tears today and accuse Cash of cultural appropriation, particularly for lifting those three songs on Side One from Black singers. No one used the term cultural appropriation at the time, but in more recent years it has been applied to stars like Elvis Presley for ripping off Big Mama Thornton and Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup, as well as against the Beatles and the Rolling Stones for stealing songs and riffs from Chuck Berry and other Black stars. Unlike the Beatles and Elvis, Cash took old songs—songs whose authorship often could not be determined—that had been handed down by many others, and reinterpreted them. No less than Blind Willie McTell acknowledged that he “jumped” songs from other writers, “but I arrange ’em my own way.” Odetta said something similar: “There are those people who are at their best when they are inventing,” she once said. “And there are people who are idea people, interpretive … I am not inventive. My category, I would think, would be embellishing invention. The interpreter.” On Blood, Sweat and Tears, Cash similarly jumped, embellished, and interpreted. The album honors the Black American folk tradition without bastardizing or commodifying it. It is worth comparing Cash’s interpretations on this album with, say, Patti Page singing Leadbelly’s “Boll Weevil” on The Ed Sullivan Show the year before, 1962. It is simply cringe-inducing. Leadbelly sang from experience, knowing the damage a boll weevil could do to a sharecropper’s family, and that feeling of desperation comes across when he sings the song—but it is also clearly about Black migration, which Leadbelly had also experienced. Patti Page, who seems never to have gotten her fingernails dirty, turned it into a children’s song, a theme to a suburban sitcom for a mass audience. That is a kind of embellishing and interpreting, too, but it is not the kind that interested Cash. The folk music that Cash liked had a sharp edge. His interpretation of most of the songs on Blood, Sweat and Tears tells the story of America’s history with racial violence. It is not for children. It is not even for Ed Sullivan.

The significance of Blood, Sweat and Tears escaped the attention of segregationists and others who may have thought that Cash, after “Boss Jack,” was one of them. The album peaked at No. 80 on the pop charts, and although Cash performed “John Henry,” “Busted,” and “Casey Jones” frequently in his shows, he said nothing publicly as the clashes between civil rights activists and racists in the South intensified in 1963, 1964, and 1965. In these years of the March on Washington, Freedom Summer, and the Selma-to-Montgomery march, Cash did nothing more to provoke the segregationists. Under pressure from Columbia, he at least managed to produce “Ring of Fire,” his first hit in years, and after that, he began devoting himself almost exclusively to making Bitter Tears (1964), his next concept album. He did record “All God’s Children Ain’t Free” as the B-side to his single “Orange Blossom Special” at the end of 1964, the year that President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act. The song, Cash said, is mostly about poor people not being equally free, but it also gestured toward prisoners and, with phrases about “opening doors” and “walking any street,” it hinted at support for civil rights. But when he fought back against the National States’ Rights Party for alleging that he was married to a Black woman, it seemed less like a principled stand than an isolated personal feud.

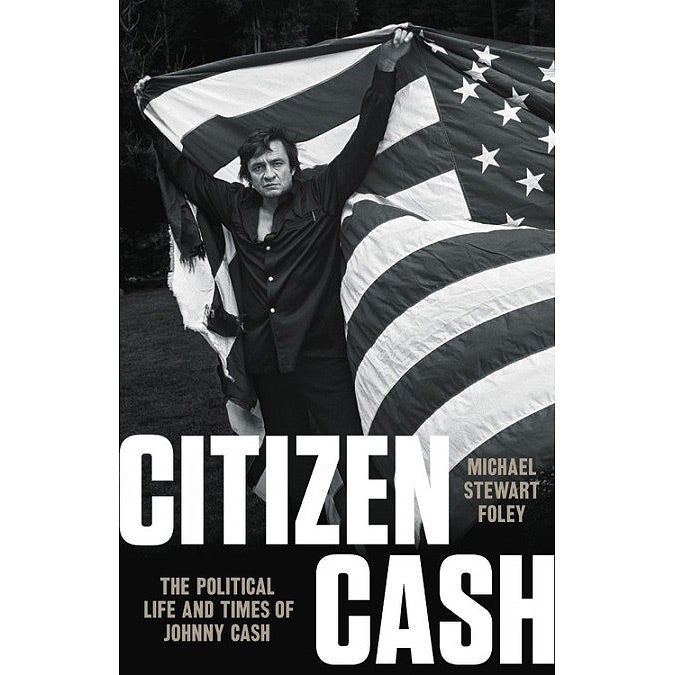

Excerpted from Citizen Cash: The Political Life and Times of Johnny Cash by Michael Stewart Foley. Copyright © 2021. Available from Basic Books, an imprint of Hachette Book Group Inc.

By Michael Stewart Foley. Basic Books.